British and American English in a Historical Perspective

You will find all these words in the following text. Find at least two synonyms for each word. You are allowed to use a dictionary if you want to. Share your answers with a partner and compare what you have found out.

assumption

authentic

proper

bemoan

establish

discrepancy

proximity

compile

straightforward

evolve

innovate

alter

Many people have for a long time been quietly bemoaning the slow death of ‘proper’ English. The finger of guilt is often pointed squarely across the Atlantic, blaming the Americans for the changes taking place in British English. This attitude was also expressed by Prince Charles when he, in March 1995, stated the following to The Times: "We must act now to ensure that English – and that, to my way of thinking, means English English – maintains its position as the world language well into the next century". He further stated that American English is "very corrupting", and that the speakers have invented "all sorts of nouns and verbs and make words that shouldn’t be".

It is a fact that American words and expressions have been introduced into British English since the first colonies were established in North America, and many defenders of the Queen's English would probably be surprised to learn just how much of their vocabulary originated in America. You will find that the language has developed and changed on both sides of the Atlantic, but contrary to popular belief, the British have been just as responsible for these changes as the Americans. Today, we see the result of these changes in British and American vocabulary, spelling, and pronunciation.

The greatest difference between British and American English is the difference in vocabulary, and there are several reasons for these discrepancies. Both countries have to a large extent been influenced by their neighbouring countries and by people settling within their borders. One example is the British name for the herb 'coriander', which has been adopted from French ('coriandre'). But if you move to the United States, they would use the Spanish word 'cilantro', reflecting their proximity to Mexico. Another example is the names of the vegetable 'courgette' (BrE) or 'zucchini' (AmE). Again, the British word is taken from French, while the American name this time comes from Italian immigrants who introduced the vegetable into American cooking.

Some of the differences in vocabulary are merely results of different preferences. You probably know that 'fall' and 'autumn' mean the same thing, but that the former is American English and the latter British English. These two words were in fact used side by side in both countries for a long time. But over time, the originally French word 'autumn' became the preferred word in Britain, while the United States gradually began to prefer the word 'fall'.

For the most part, the lexical differences have developed as an inevitable result of centuries of separation and independent development. Whenever people on one side of the Atlantic needed a new word, they simply invented one without bothering to investigate whether speakers on the other side of the Atlantic used another word for the same thing. Words like 'railway'- / -'railroad', 'film'- / -'movie', and 'car'- / -'automobile' have developed independently on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

The interesting thing is that many words that we today categorise as typically American words are, in fact, words that historically were used in Britain first. For example, words like 'gotten', 'diaper', 'soccer', 'trash', 'sidewalk' and 'candy' all have British origin. While British English have found other words describing the same things, these words have become the preferred words in North America.

Also when it comes to spelling, the American version is sometimes closer to the original. For example, the suffix -ize ('organize', 'realize', 'civilize'…) was in fact the original British spelling until around the 18th century. In America, they kept the original spelling, but in Britain they also allowed for the suffix -ise ('organise', 'realise', 'civilise'…). The same thing happened to words ending in -er ('theater', 'center'…). The British spelling was changed to -re ('theatre', 'centre'), giving it a French touch, while the Americans kept the original spelling.

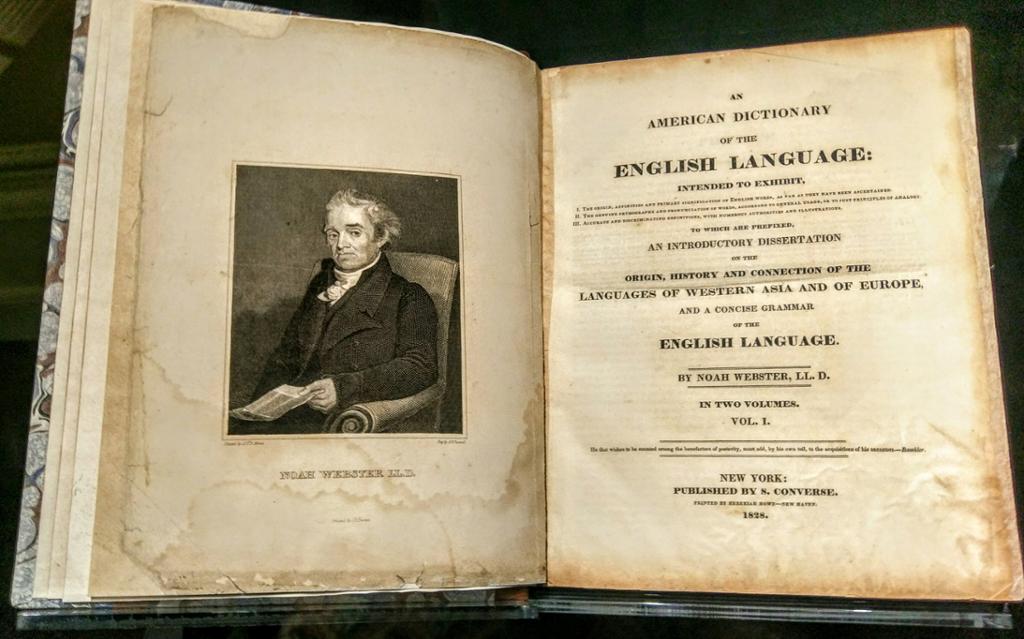

However, Americans have also been responsible for some changes. When America received their independence from Britain in 1776, an American academic, Noah Webster, saw that political independence also provided an opportunity for linguistic independence, and he compiled the famous Webster Dictionary. Webster wanted American English spelling to be straightforward and easy, and he attempted to simplify the language by dropping what he felt were unnecessary letters. He also wanted American English spelling to be different from British spelling as a way of demonstrating that America was an independent country – almost like a form of political protest. As a result, American and British spelling is today different in words like 'flavor'- / -'flavour', 'armor'- / -'armour', 'anemic'- / -'anaemic', and 'catalog'- / -'catalogue'.

Listening to British and American English, the most distinct difference in pronunciation is the /r/ sound. Standard British English is a so-called non-rhotic variant, which means that the consonant /r/ disappears from speech everywhere except before a vowel. American English, on the other hand, is a rhotic language, where the /r/ sound is pronounced throughout the word. You can easily hear the difference in words like 'far', 'dark', 'bird' and 'further', where Americans would pronounce the /r/ sound while a Standard British speaker would leave it out. (However, it should be noted that there are regional exceptions to these patterns, as some of the accents of south-eastern England, plus the accents of Scotland and Ireland, are rhotic. Also, some areas of the American Southeast, plus Boston, are non-rhotic.)

Interestingly, the British accent used to be rhotic, like the present-day American accent, but the /r/ has now completely disappeared from Standard British English. This change started at the end of the 17th century or early 18th century, and Americans who returned to Britain at the end of the 18th century reported with surprise this significant change in the pronunciation of the language.

The pronunciation of American English has most likely evolved less than British English since the first settlers arrived in America, and it has retained many elements of the language that used to be spoken in Britain before the colonisation. So, perhaps the plays of Shakespeare would sound more authentic performed in Chicago than in London?

Languages change and evolve all the time. They are organic, growing, adapting creatures, and the languages spoken in Britain and the United States today are both vastly different from the languages that were spoken 300 years ago. Throughout time, both the Americans and the British have been involved in changing the English language, and contrary to popular belief, the British have been just as active in changing it as the Americans. Words and expressions have always been exchanged across borders, and the languages have been altered and adapted by their users. Such borrowings only enrich the language, making it more wide-ranging and expressive. So, is 'proper' English dying? Not at all: it is developing.

Relatert innhold

Tasks that help you see the difference between British and American English