The Infodemic: A Mishmash of Truths, Fake News, and Conspiracy Theories

- Explain the difference between misinformation and disinformation.

- In the box below, you will find phrases and words that are related to the article. Find two-three synonyms for every word in bold.

As the coronavirus spread across the world, so did rampant misinformation and disinformation about the illness. In the first few months of the pandemic, we experienced an explosion of fake news and conspiracy theories, which were in particular shared on social media. We faced an infodemic, an overabundance of information, some accurate and some not, that made it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they needed it.

The problem with this surge of information was that in many cases, the information presented was downright dangerous. In fact, according to a study published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, about 800 people died in the first three months of 2020, and 5800 were admitted to hospital, as a result of false information and dangerous medical advice on social media. Some people believed that drinking methanol or alcohol-based cleaning products would kill the virus, while others resorted to eating large amounts of garlic or ingesting large quantities of vitamins. Some people believed that snorting cocaine would protect them. There were also examples of people in India drinking cow urine and applying cow dung on the body to cure COVID-19, believing it would only work if it came from Indian cows. Needless to say, the effect was not what they had hoped for.

Some of the fake medical advice that were presented to people could be harmful and even fatal. We also encountered conspiracy theories that were downright sinister. The most widespread conspiracy theory linked to COVID-19 claimed that the pandemic was part of a strategy conceived by global elites, among them Bill Gates, to roll out vaccinations with tracking chips that would later be activated by 5G, the next-generation wireless network technology. This would allow governments to monitor the movement of billions of people. In fact, a Yahoo News/YouGov survey found that 28% (44% Republicans, 19% Democrats) of the adult population of the United States believed that Bill Gates had seeded the virus for his own nefarious purposes.

Another conspiracy theory was that the virus was engineered in a laboratory in Wuhan, the city in China where the outbreak began. Accidentally or intentionally, the virus was then released into the world. Even former President Trump claimed that he had seen evidence that the coronavirus had originated in a Chinese laboratory, despite US government officials and medical professionals having rejected this theory on multiple occasions.

It is not difficult to understand the frustration of World Health Organisation Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus when he later stated in a press briefing that “We’re not just battling the virus. We’re also battling the trolls and conspiracy theorists that push misinformation and undermine the outbreak response.”

Conspiracy theories tend to become widespread in times of crisis and turmoil, and they seem to be triggered to a large extent by collective fear, uncertainty, and lack of information and control. People have a basic need for knowledge, and to feel safe, secure, and in control of their lives, so in times of economic, political, or social crisis, the temptation to fall back on conspiracy theories to rationalise the unexpected is especially great.

We may laugh off the most improbable conspiracy theories, such as the claim that the moon landing was a hoax, that the Earth is flat, and that Australia doesn’t exist. But conspiracy theories can also be very harmful to both believers and society in general. During the pandemic, the conviction that 5G was the culprit behind COVID-19 prompted numerous attacks against mobile phone towers across Europe. In fact, in April/May 2020, 77 towers were burnt down in the United Kingdom alone. Even more serious was the dramatic increase in racial attacks on East Asian people in Europe and the United States during the pandemic. And one of the most serious conspiracy theories, that COVID-19 is no more than a flu, was repeated so many times by some political leaders, that it most likely contributed to much higher infection and death rates in seveal countries.

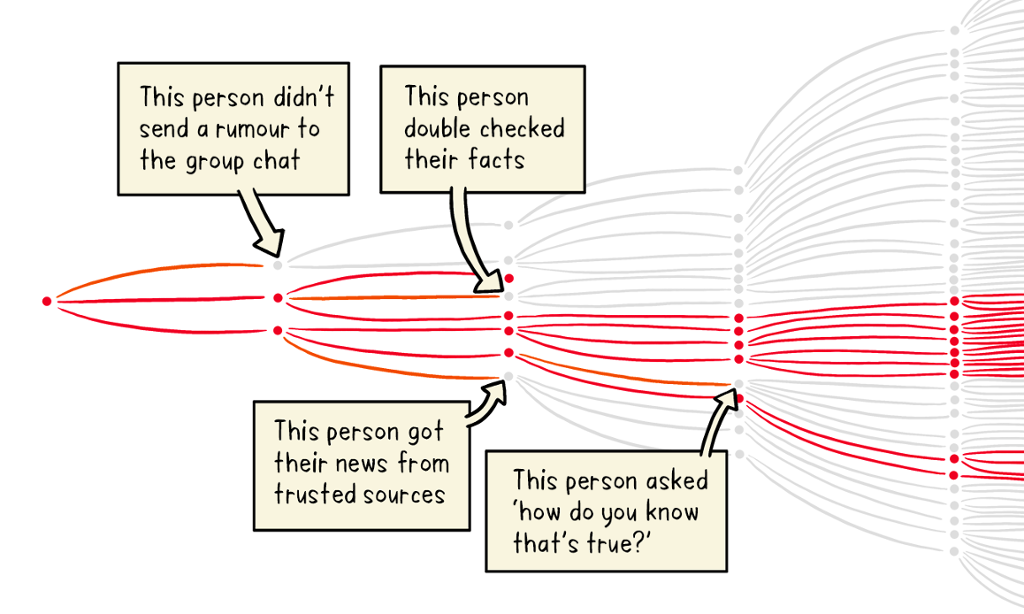

It is really important to be aware of the dangers of mis- and disinformation on the internet and to do what you can to stop the spread. If you share fake news and conspiracy theories with your friends and family, and then a few of them pass this on to more of their friends and family, then potentially harmful or dangerous information may be taking over everyone’s newsfeed before you know it. However, it is possible to slow down the spread of such mis- and disinformation. Before you pass on information that may seem a bit dodgy, ask yourself: Why am I sharing this? How do I know it's true? Can I trust the source? Whose agenda might I be supporting by sharing this? We can stop the spread of stop mis- and disinformation, just as we can stop the spread of a virus.

In the following film, made by NDLA, you will meet Suzie, Maria, and Ray as they discuss different ways to fight the corona virus - some ways more sensible than others. You will also hear researcher Karoline Andrea Ihlebæk from Oslo Met explain why fake news has become so prominent in the past few years and what you can do to detect fake news. Watch the film before you move on to the tasks.

Guoskevaš sisdoallu

Tasks related to the article The Infodemic: A mishmash of truths, fake news and conspiracy theories.