The Fight for Women's Right to Vote

The Fight for Women's Right to Vote

In Victorian England, women were dependent on men: she needed a father, brother, or husband to represent her interests. Marriage and children were seen as a woman's purpose and destiny. In the marriage ceremony, the woman vowed to obey her husband. Once a woman married, she was at the mercy of her husband who took ownership of all her material belongings. While most men treated their wives with respect, those who did not were able to abuse their power without intervention.

Women did not have the right to vote, sue, or, if they were married, own property. Through the 19th century, some laws were passed that were beneficial for women. For instance, in 1839, a law was passed giving women custody of children under the age of seven in the event of a separation. In 1857, women were given the right to divorce husbands who were cruel or had abandoned them. In 1870, women were allowed to keep money they had earned themselves. Although these were important laws for women, they were seldom enforced. The Victorian attitude towards women was that their place was at home, looking after their husband and children. Queen Victoria herself said, 'Let women be what God intended, a helpmate for man, but with totally different duties and vocations.'

For upper and middle-class women, it was unthinkable that they would have a career. Servants did all the physical work for them. Consequently, they had an abundance of time on their hands and their days were often spent doing crafts like embroidery, visiting friends and family, and perhaps writing letters. These girls were educated by governesses who taught them reading, writing and arithmetic, and sometimes French. Being a governess was one of the few positions a middle-class woman was allowed to have. They were poorly paid and often treated poorly, too.

Domestic service was the only career option open to working-class women, besides working in a factory or as a farm labourer. Working-class women led lives of strife, often giving birth to at least eight children and having to work 14-hour days – in addition to having sole responsibility for all the cooking and housework.

What women of all social classes had in common was their lack of opportunity to carve out their own paths in life. Without the right to vote, women had no chance of changing their position in society – or that of their daughters. Women’s suffrage therefore became the most important goal for women of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The organised campaign for women’s suffrage in England began in 1867, when the philosopher John Stuart Mill presented a petition in Parliament calling for inclusion of female enfranchisement in the Reform Act of the same year. The Reform Act was passed without this inclusion, but the idea had now been voiced by a highly respected man in Parliament. That same year, Lydia Becker founded the first women’s suffrage committee in Manchester. In the course of the next few years, several such committees were formed, and in 1897, they joined forces as the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) with Millicent Fawcett as its leader.

However, real change took a long time. Every attempt to pass a bill to extend the vote to women was defeated. Frustrated by the situation, some women adopted more militant methods of protest, and in 1903, Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters, Christabel and Sylvia, founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). Along with their followers, called suffragettes, they disrupted political meetings, staged protest marches, and smashed windows in shops and in government buildings. They even bombed or set fire to a number of buildings, which resulted in the death of at least 5 people.

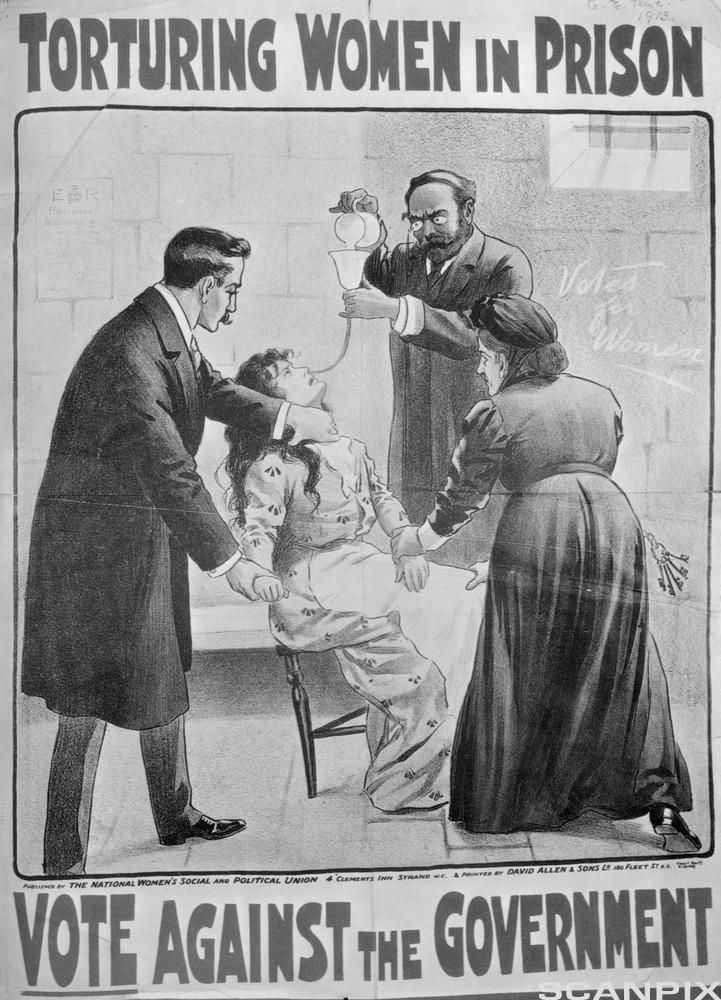

Suffragettes who were arrested drew more attention to their cause by going on hunger strikes, and the authorities did what they could to avoid creating martyrs by force-feeding them. In 1913, a young woman named Emily Davison threw herself in front of King George V’s horse at the Epsom Derby and was killed, thereby providing the suffragettes with the martyr they believed they needed.

By this time, members of both the peaceful NUWSS and the militant WSPU believed that the 1914 election would result in government backing of their common cause. However, the First World War broke out that same year, and both organisations ceased all political activity. For the duration of the war, the women of Britain concentrated on the war effort – many of them doing the jobs that men had done before they went off to war.

On February 6, 1918, Parliament passed the Representation of the People Act, giving women over the age of 30 who owned property the right to vote. It has been assumed that this act was passed in gratitude for the role women had played during the war. It is, however, probable that the women's suffrage movement constituted a significant reason for passing the act: Britain was exhausted from the war, and the authorities wanted to avoid a return to the violence instigated by the pre-war suffragette movement.

In 1928, the government extended the franchise to include all women over the age of 21, regardless of property.

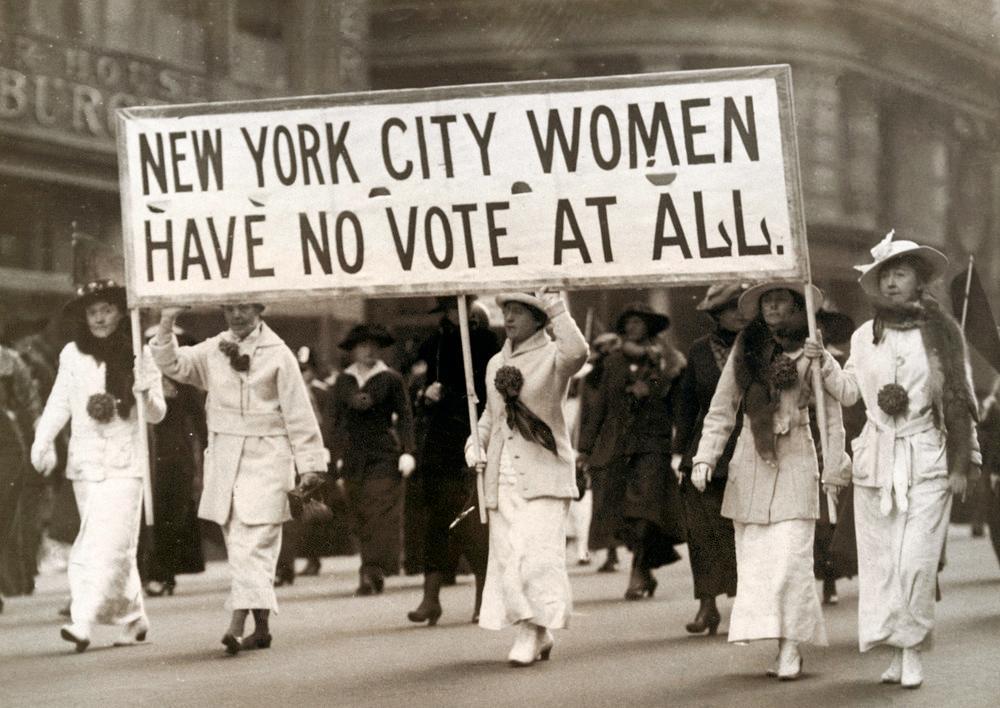

The fight for women’s suffrage was not just a British phenomenon. It is inextricably linked to the American movement, which began as early as in 1848, when Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Mott and three other women organised the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York. In 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment to the American Constitution granted American women the right to vote. Throughout these years, American and British suffragists were closely connected - they visited each other, and encouraged and helped each other.

In 1893, New Zealand was the first country in the world to give women the right to vote. Some European countries also gave women that right relatively early: Finland in 1906, Norway in 1913, and Denmark and Iceland in 1915. Switzerland, however, did not give women the vote until 1971, and Lichtenstein was the last country in Europe to follow suit in 1984. Throughout the 20th century, countries all over the world implemented universal suffrage. In 2015, Saudi Arabia was the last country that allowed women the right to vote.

However, even though women all over the world today officially have the right to vote, it doesn't mean that all women have the possibility to do so. In some countries, such as Afghanistan and Pakistan, women are often not allowed to leave their home without permission from a guardian and they are therefore often barred from voting by their husbands and village elders. In the 2016 election in Uganda, there were several examples of violence against women at the voting polls, and this discouraged many women from voting. In the rural areas of Kenya, the distance to the registration centres is often very far, and this makes it difficult for women who are also responsible for all household chores and looking after the children. The societal barriers blocking women from voting are usually stronger than the legislative guarantees, and there are still many countries across the Middle East, Africa, and Asia where women are subordinate to men and are consequently disenfranchised, regardless of what the law states.

Go back to the pre-reading activity. Can you still remember the meaning of the words? Work with a partner.

Relatert innhald

A set of tasks based on the article 'The Fight for Women's Right to Vote'.

In every country in the world women continue to be paid less than men for comparable work. What can we do to close the gap?