Pidgin and Creole Languages

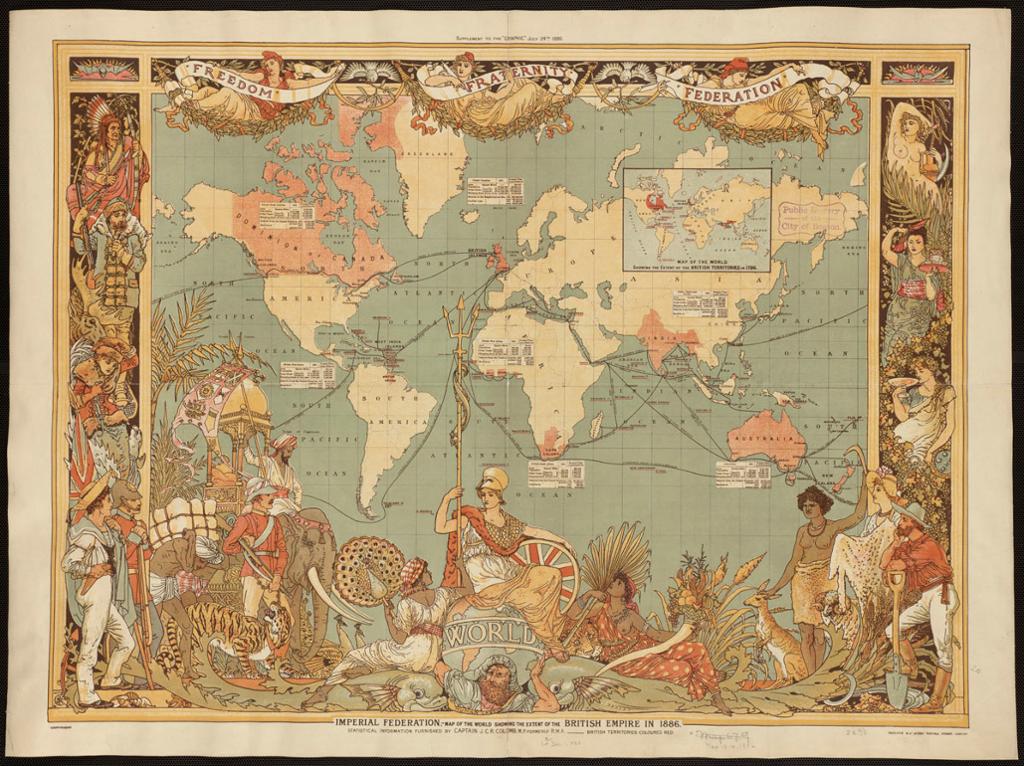

During the British colonial period, trade routes and colonies were established around the world in areas where few or none mastered the English language. This was a challenge for the British and the natives alike – they needed a common language, a lingua franca, that allowed parties could communicate. New forms of communication developed: words and expressions from two or more languages were mixed into a language that enabled people to communicate.

These languages are called pidgin languages. Pidgins are improvised languages, stripped of grammar and with a limited vocabulary. The languages' function was to facilitate trading and bartering between European tradesmen and the native population. In other words, a pidgin language is not a native language; it is the first-generation version of a language that forms between native speakers of different languages – a makeshift communication bridge, if you will. They are primarily spoken languages, there is no standardised form, and many local varieties exist.

Sometimes, pidgin languages are passed down to a second generation of speakers who adopt it as their native language. The language is then formalised and standardised, and the makeshift communication bridge is fortified into a more robust structure with a fully developed grammar and syntax. It goes from being a pidgin language to becoming a creole language.

Today, you will find a concentration of English-based pidgin in Western Africa, where it is one of the most widely-spoken languages across the region. In fact, up to 75 million people in Nigeria alone – close to half the population – use Nigerian Pidgin as a second language. However, it is not recognised as an official language.

This did not stop the BBC from launching a pidgin digital service for its West African audience in 2016. The key challenge for the BBC was that West African Pidgin is largely a spoken language and does not have a commonly agreed upon spelling or written format. Gradually, they have tried to standardise the language into a form that most pidgin speakers in the region can accept. It soon became immensely popular among its audience, and many believe that this service will actually help West African Pidgin develop into a more formalised language – a creole language.

By the time a pidgin language becomes a creole language, the language has developed enough of its own characteristics to have a distinct grammar of its own, and this is what has happened in the Caribbean, where the pidgin languages that once existed have become creole languages.

However, most Caribbean countries still use their respective colonial power’s language for official purposes, be it French, Spanish, Dutch, or English. In some countries, however, there is a movement away from this practice. In Jamaica, there has been serious deliberation about introducing Jamaican Patois (Creole) in schools, as it is believed that it is best for children to learn in their first language. Also, it has been argued that Patois represents the region’s hybrid culture and is therefore the authentic expression of their identity. Patois should therefore be the preferred language in schools. But so far, pupils still receive their education in Standard English.

Jamaican Patois does not have any legal status as an official language in Jamaica, and it is not regarded as an acceptable language of communication in the public sector, including schools. This is partly because of the stigma attached to the language – it is regarded as the language spoken by the uneducated class. But there is also a question of what is best for the development of the country. Many of these arguments are presented in this letter to the editor taken from the Jamaican newspaper The Gleaner:

How will Patois help us develop our country? How will Patois help our young people read and write standard English when all around them they hear nothing but broken English? How will Patois help tourists communicate with us? How will Patois help our country become the place to live, work, learn and retire? How will Patois bring in more investors to our country? How will Patois help us gain and keep traction on the global stage?

Eloise Brunner

We often see a stigma attached to creole languages, including Jamaican Patois, even when it is spoken as a mother tongue by the majority of the native population. However, we should remember that these languages have long histories and represent unique cultures and identities in their respective countries. They are part of the diversity that exists in the English language and are languages in their own rights.

Relatert innhold

Tasks related to the article 'Pidgin and Creole languages'