Creating Your Own Short Story

As you work your way through this text, you will encounter a number of tasks. Work on the tasks by yourself before you share your work in a group.

It is easiest to keep going back to the same group each time. This will also help you see how your own writing and the work of your fellow students develop.

Give each other supportive, positive feedback. You may for example point out two things that you really liked and make one suggestion for improvement.

If you need tips on how to give good peer feedback you can watch this video from the Odyssey Learning Project on YouTube: Link to film: "What it Means to be a Peer Reviewer".

Writing short stories depends on being able to say as much as possible with as few words as possible. It is said that Ernest Hemingway once, to win a bet, wrote a short story that was just 6 words long. Read the 6 word short story below. Do you agree that this qualifies as a short story?

For sale: baby shoes. Never worn.

Task 1. 50 word limit:

In this task the challenge is to be able to create a story when you have very few words at your disposal.

- Write a story about yourself in 50 words or less.

- Make sure it is a story; something must happen in the text.

- Do not exceed the 50-word limit.

When you have finished writing, share your text in a group. Give each other feedback that highlights what was good about the story.

Characterisation is the way an author brings a character to life. This can be done through direct characterisation, where the author describes the character: what do they look like, what do they wear, what is their personality like, and so on. It can also be done through indirect characterisation: describing things the character says or does that reveal something about them.

He was the sort of person who stood on mountaintops during thunderstorms in wet copper armour shouting "All the Gods are bastards".

Sir Terry Pratchett, The Colour of Magic.

Task 2. Using imagery to describe a character:

Think of a character, and use imagery to describe them. You can for example use a simile or a metaphor. (If you have trouble thinking of a character you can use imagery to describe someone you know.)

When you have made the description share it in the group. What do the group members think your character is like, based on your description?

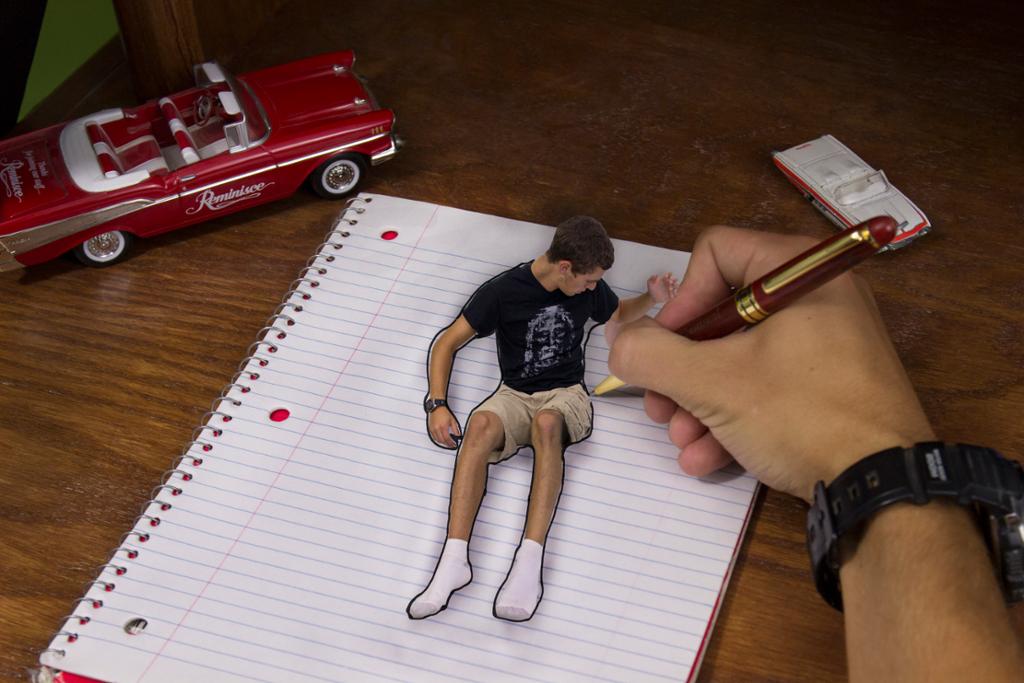

Task 3. Picture the person:

Think about the person you wrote about in Task 2: What is the person wearing? What do they carry in their pockets?

- Make a list.

- Look at what you have listed: What do the items say about the person?

- Share your list with your group. What do they think the items say about the person?

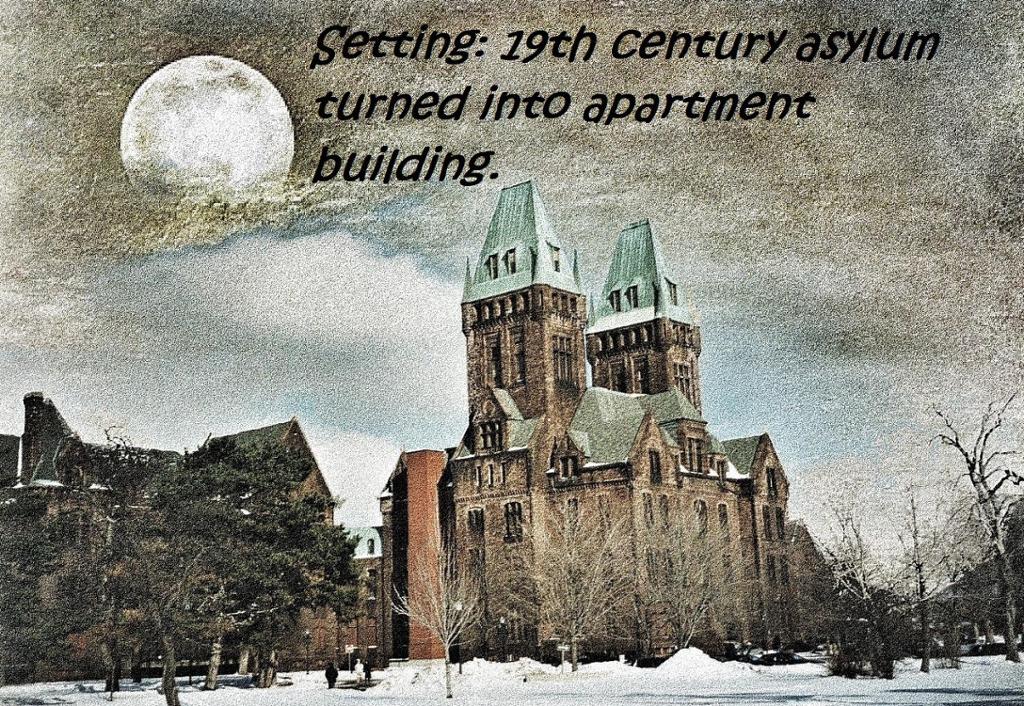

The setting is where and when a story takes place.

The setting can encompass a time of year, a time of day, a certain century, it can be in England, in a house, in a room, etc.

If you are able to describe a realistic setting, it will help the readers picture the story in their minds.

Task 4. Explore setting:

Use the character you have written about in task 2 and 3, and place them in a setting that would be surprising or strange to them.

(The last place you’d expect to meet the person / an unlikely situation for them to be in.)

Write a few paragraphs about what happens to the person in this setting.

Share what you have written with your group and explain why the situation would be unusual for the character. Give and get feedback.

Being able to create mood and atmosphere in the story is important. One way to do this is to describe sounds and smells, or to describe how something feels to touch. Engaging the readers' senses draws on both memory and imagination and makes the setting and situations you describe seem more real.

She has come to believe the homes of sad or hateful people smell different. When people have sadness or hate inside them, it comes out in a miasma. Dr. Hammond’s house smells like a form of slow poison has been hanging in the air for years. She has a sudden conviction that if she lifted all the furniture in his house she would find layers of squished black bugs underneath

Rene Denfeld, The Enchanted.

Task 5. Smell, sound and touch:

If you want to give your readers the feeling that they can smell, hear, and/or touch the things listed below, how would you describe them? Be creative, and don't shy away from using imagery.

- sleeping in freshly laundered sheets

- dogs barking

- spring morning

- lion's cage at the zoo

- being by the ocean

- a marching band practicing

- entering a pizza bakery when you are very hungry

Share what you have written in groups. Did any of the descriptions surprise you? Give and get feedback.

Usually, when we talk about conflict, we think of people having an argument or a fight. In literature, the conflict is an obstacle to be overcome and the thing that sets events in motion and carries the action forwards. For example, in Jane Austen's novels the conflict can be a woman's desire to marry well.

It is common to divide conflict into six main types in literature:

- A character having a conflict with themselves. This is a story where the main character must overcome something within themselves in order for the story to be resolved.

- Two or more characters having a conflict with each other. This is easy to understand. Two or more characters want different things and come into conflict with each other because of that.

- Character against nature. This is where a character comes into conflict with a natural phenomenon, wild animals, storms, rough terrain and so on.

- Character against the supernatural. Many interesting and fun stories are set in the realm of fantasy, where the character may battle ghouls and ghosts, wizards or trolls.

- Character against technology. This is especially common in science fiction, but other stories may also describe how a character comes into conflict with new technology.

- Character against society. It can be hard to fit in, and many stories centre around characters who are outsiders in the world they live in.

Task 6. Create a conflict:

Think about a conflict that your character may have. Write a simple timeline for how you would like the conflict to play out and be resolved. It is also possible to have an unresolved conflict, by having an open ending.

Sometimes a story just comes to us, but a lot of the time we will have to plan it out. There are several ways to plan out a story. You can make a mind map where you write down key words about conflict, setting, characters, etc. Another option is to start with an idea, put pen to paper, and see where your writing takes you – and when you have gotten a rough idea, add key words to how you see it progressing and ending.

Task 7. Make plans for two short stories:

From the list of titles, pick two and make a plan for how you would write each story. Think about characters, setting, and conflict. You may use a mind map, or just write down key words.

- Vitamins

- How to Talk to Your Mother

- Small Good Things

- Cathedral

- Feathers

- Lost in the Middle of Everywhere

- Boxes

- The Impossible Escape

Keep the Home Fires Burning

Share your writing in your group, and give and receive help to improve your plans. Think about what will make the stories as interesting as possible.

As any author will tell you, the only way to become a writer is to write. When it comes to writing fiction, practice is unlikely to ever make perfect, as readers will have different opinions of your work no matter how well you write. But practice will make you better. If you feel you have no imagination, you can draw inspiration from real life. If you feel you have a lot of imagination, set it free and see where it takes you.

Task 8. Write a short story:

Choose one of the two stories you planned and write the story in full. Share what you have written in the group, and get suggestions for improvements before you hand it in.

It can be difficult to assess short stories because our enjoyment of them will in part be a result of personal preferences. In the expandable box below, we point out some elements you may consider when assessing a classmate’s short story, or when you are revising your own.