South African English

In order to understand the position of SAE in South Africa today, we have to go a few years back in time.

Historically, there have been two competing ‘white’ languages in South Africa since white settlement started in the 17th century: South African English and Afrikaans. Afrikaans is based on Dutch, as Dutch traders were the first white settlers in South Africa in the mid-1600s. The British occupied the Dutch colony in the late 1700s and began settling there in the 1820s. Afrikaans was the first language of the majority of the white population, including those in power, and it acted as an important symbol of identity for everyone with Afrikaner background. SAE, on the other hand, was used by the remaining whites of British background but also by a steadily increasing number of blacks.

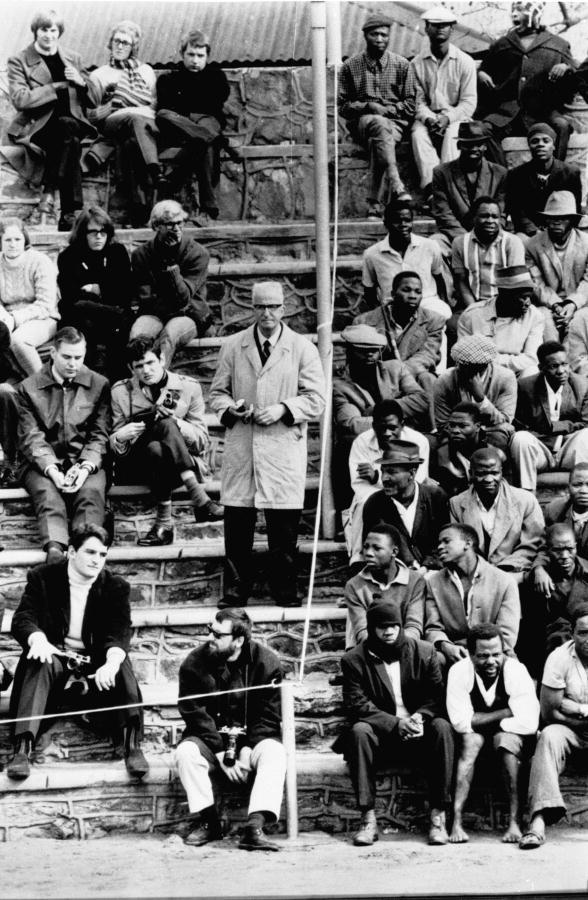

From 1948 until 1994 South Africa had a system of racial segregation called apartheid. Apartheid was based on ideas of white supremacy, and was an oppressive, authoritarian system. The system ensured that South Africa was dominated politically, socially, and economically by the nation's minority white population.

During Apartheid, demographic differences in the use of the languages were further reinforced, and we could clearly see a linguistic side to the political division that existed in the country. The rise of Afrikaner nationalism during the apartheid era pushed the Afrikaans language to the head of the table. The Afrikaner government ensured that the civil service and other state organs were filled with increasing numbers of Afrikaners. More and more official businesses were conducted in Afrikaans, where SAE had previously been preferred. And in 1953, the Bantu Education Act was introduced, replacing SAE with Afrikaans as the dominant language of education. The language was used deliberately during Apartheid to create a divide between races and came to be known as the colonial language of the white Afrikaner oppressor.

On the other side of the table, you would find the black majority of South Africa rebelling against an oppressive regime. For them, SAE became the ideal language to use in the conflict. They all spoke a variety of African languages and used SAE as a lingua franca to cross the language barriers. Equally important, English was an international language, and was used as a way to reach out to the world to show their suffering. SAE became a unifying force for black South Africans, as well as a cry for help and support to the international community.

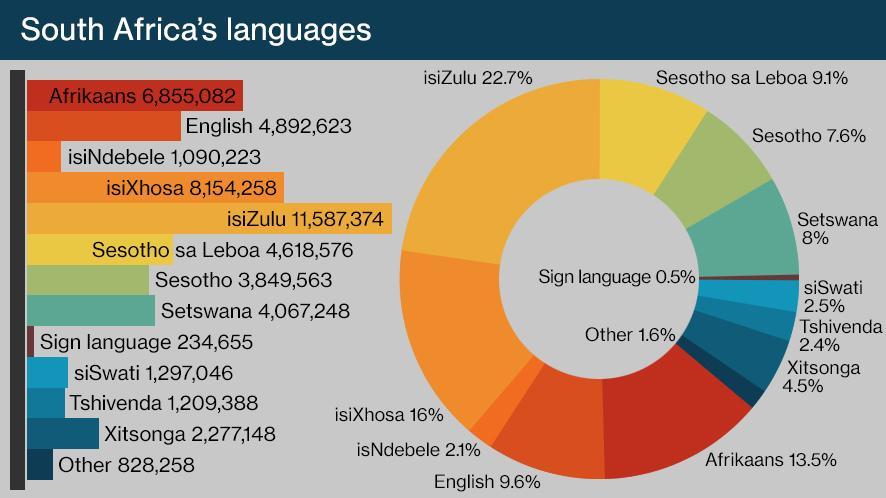

In 1994, the apartheid era ended. This brought about rapid changes in the balance between SAE and Afrikaans in public life. Even though South Africa has eleven official languages, and multilingualism is entrenched in the constitution, SAE is now the preferred language in government, media, and business. It is also the dominant language in higher education. This is partly because SAE is regarded as a more ‘neutral’ language for the majority of South Africans. Also, it is an international language that facilitates communication with the rest of the world and makes it easier for South African businesses to position themselves in the world market. Another reason SAE is important is that administering eleven different official languages is almost impossible and extremely costly in terms of translations and printings.

SAE uses the British grammatical system, but as a spoken language SAE has taken on a number of peculiarities, as it has been mixed with a variety of accents and languages.

Accent and pronunciation

As a result of apartheid, there is no single, reasonably uniform South African English accent. Until the 1990s, communities lived and were educated separately according to ethnic background, and this resulted in many varieties of English: white Afrikaans-speaking SAE, white English-speaking SAE, black African SAE, Indian SAE, and so on. However, since children of all races and backgrounds are now being educated together, the previous ethnically determined differences are in the process of breaking down.

The South African accent has similarities to British accents in that it is non-rhotic. This means that the consonant /r/ is pronounced only when it comes in the beginning of a word (e.g. 'road', 'real') or if it precedes a vowel (e.g. 'moral', 'borrow'). In all other places, it is pronounced as a neutral vowel (e.g. 'market', 'score')

However, you will find some phonetic features that distinguish South African English from British English. For example, the vowel /a/ is often pronounced as ‘eh’, which means that South Africans would speak with a ‘South Efrican Eccent’

Slang and unique words:

SAE has a number of slang words and phrases that set it apart from other English varieties. For example, the word now doesn’t always mean what you think it means. If you say that you will do something 'now-now' or 'just now', it means that you will do something later, in a little while.

'Jawelnofine' (yes-well-no-fine) is a typical South African expression of resignation, used when an individual is giving up on something.

Another word that is a bit confusing is 'shame'. This is an endearing term that expresses sympathy or admiration: 'Shame man, poor girl', 'Shame, she's so cute'.

And if you go driving in South Africa, you have to remember to stop at the 'robot' (traffic light).

Loanwords:

South Africa is a melting pot for people of different cultures and languages, and the South African English lexicon is peppered with words and phrases from other South African languages. Particularly Afrikaans words such as dorp ('village'), kloof ('valley'), braai ('barbecue'), and veld ('open field) have made their way into SAE. But you will also find words from Afr'ican languages, such as bonsella ('tip', 'bonus'), indaba ('discussion'), tsetse (a bloodsucking fly) and tsotsi (a young urban criminal).

All these words and expressions make SAE a unique variant of English, and a bit different from what you are used to. If you now move on to the tasks, you will find more South African expressions that can be useful to know if you ever go travelling in South Africa.

Related content

Tasks related to the article about South African English (SAE)