In 1851 Britain decided to celebrate itself in the Great Exhibition, an exhibition that displayed the nation’s achievements and prosperity. It turned out to be a manifestation of success and progress and it took place inside a huge iron and glass construction called Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park. It showed the world that Britain truly was “the workshop of the world” and that its expansionist nature was highly rewarding. Thus, much of the Victorian culture evolved around the ideas of trade and economic development, in which overseas territories continued to play central roles. In the decades following the Great Exhibition, it was not only trade that became pivotal for Britain, but also the so-called civilised countries themselves where they traded and had settled.

The Raj

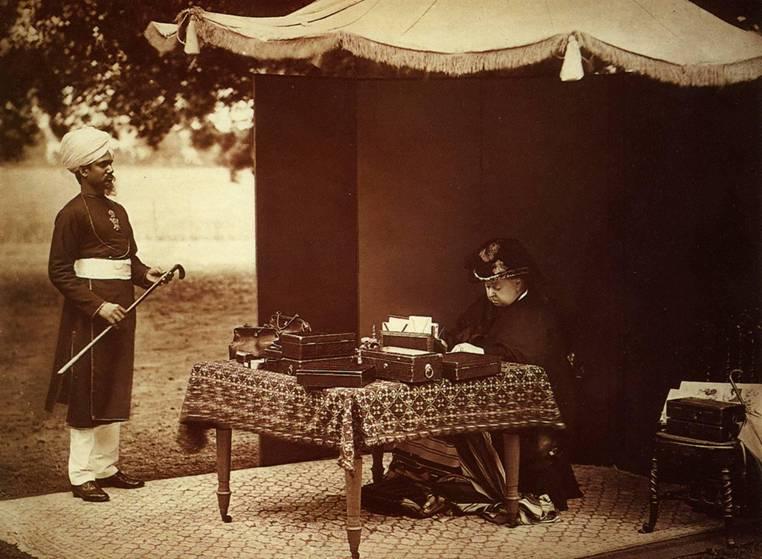

In the sense that the thirteen American colonies were central for the first Empire, it is no exaggeration to claim that India was “the jewel in the crown” in the second. The East India Company had been set up already in 1600, under Queen Elizabeth I, showing the long and successful trading history with India and the Far East. With the East India Company firmly established on the Indian subcontinent, India became the centre of trade in the area, and Britain had trading posts in China, Ceylon and on the sea route to India, especially along the African coast. In the mid-19th century tension in India increased, and in 1857 Indian soldiers organised a mutiny. In fear of losing markets and commercial interests, Britain decided to take full control of the vast country by setting up an Indian administration on behalf of the British government. The British Indian administration was called “The Raj” and Queen Victoria (1836-1901) became the “Empress of India” in 1876.

The Four Cs

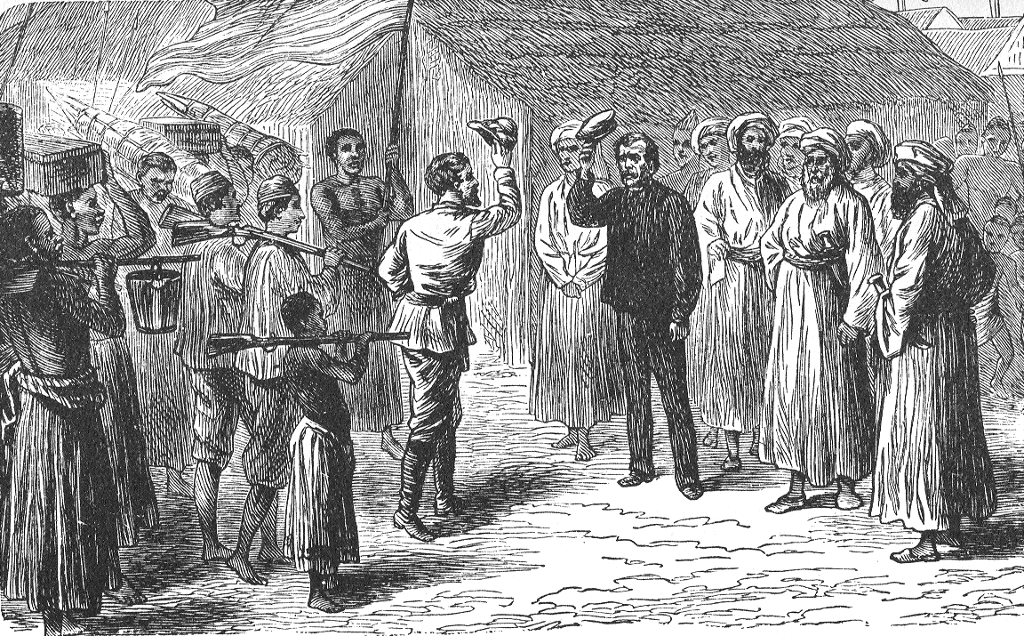

Though many areas in the East, the Far East, the Caribbean and North and South America had changed hands between the Portuguese, the Spanish, the Dutch and the British throughout the centuries, Africa had attracted less interest from European powers. The continent was enormous, regarded as impenetrable and full of fatal diseases. Therefore, European trading posts had been established on the coast in order to avoid the African interior, and African middlemen were used, for example during the peak of the slave trade in the 18th century. But in the mid-Victorian period, Africa commenced to attract more and more attention, and a typical embodiment of many of the Victorian values was David Livingstone, the missionary and explorer. As a man of his time, he advocated the four Cs: Christianity, Commerce, Colonialisation and Civilisation. Missing in Africa, he became famous for his rescuer, Henry Morten Stanley's, phrase, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”

The Scramble for Africa

During the Scramble for Africa, launched in the wake of the Berlin Conference in 1884/5, Britain along with the other European nations determined to take what they saw as the civilised approach to the colonisation of Africa. In Berlin, the present European heads of state carved up Africa and divided the continent between them, without any Africans being present. Under the slogan “Cape to Cairo”, Britain expanded their possessions in Africa and aimed at constructing a railway line from Cairo in Egypt in the north to the Cape Province in the south. At the same time, the French sought to safeguard trade along the east-west axis, causing the two most powerful European colonial nations to meet head-on. And they did in Fashoda, in the Sudan, in 1898.

The territorial disputes nearly ended in warfare, but were eventually solved diplomatically to Britain’s benefit. Britain did, however, shelve its ambition of a north-south railway as too many political, geographical and economic obstacles proved the project too ambitious. Cecil Rhodes, a British imperialist and one of the foremost spokesmen for colonial Africa and an enthusiastic defender of the railway line, was the personification of the British dream scenario in Africa. He was a good example of a business magnate who made fortunes in diamond mining in southern Africa.