British Values and Identity

Vocabulary

denotation, connotation, entity, misleading, annex, partition, current, oppose, conjunction, significant, awareness, superimpose, aspiration, bond, commerce, furthermore, fortify, code of conduct, strike a chord, falter, scepticism, focal point

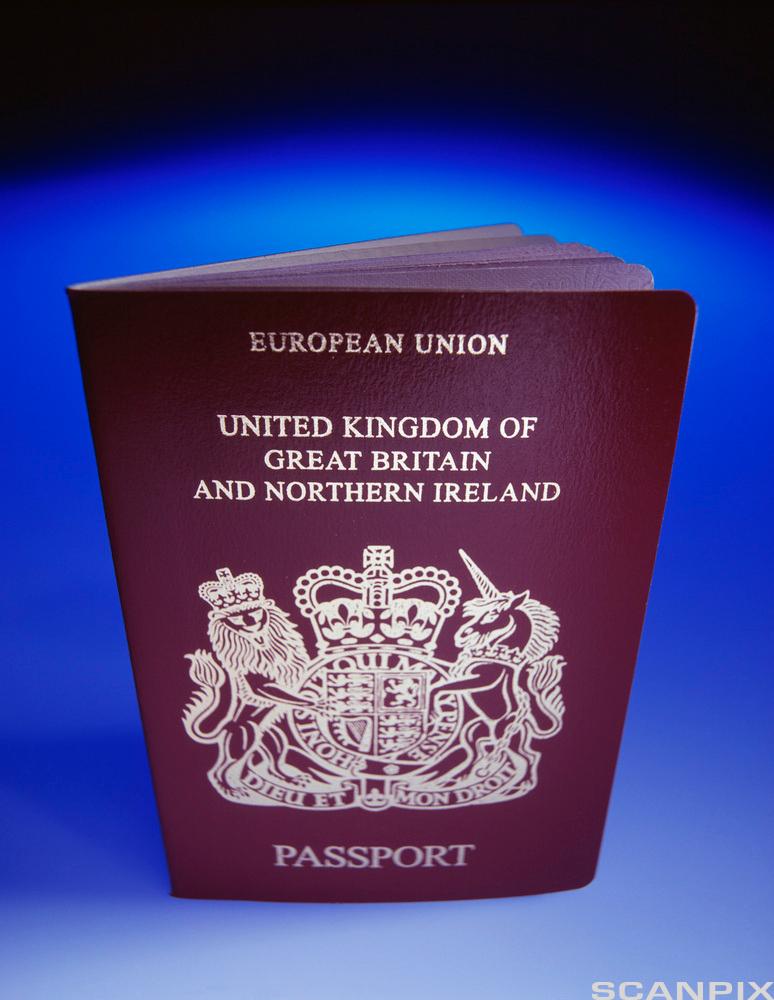

The United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the official name of the geographical entity we normally call Britain. The Union came about in four stages, and it consists of four nations: Wales, Scotland, England and Northern Ireland. The term Britain is often misleadingly replaced with England. The UK refers to the whole Union, while Great Britain only refers to the British mainland, excluding Northern Ireland.

In 1707, the two countries Scotland and England were politically united. Already in the 1530s, Wales had been annexed by England and Ireland was taken into the Union in 1801. When Ireland was partitioned in 1921, Northern Ireland remained part of the Union while the south gained its independence. This historical development accounts for the current official name of the Union and it underlines that the four nations all have their separate histories with their own values and identities. Thus, when examining British national identity, it is necessary to locate issues, features or events that have bound the four nations together. In other words, factors which have contributed to building up and strengthening the bond between Britons in the four nations as opposed to or in conjunction with the individual national identities.

Britishness and the Union

Interestingly, there are many important issues, both social and political, relating to the Union as a whole. It is worth noting that the formation of the British identity was, in the Union’s early phase, just as significant as the creation of the political unit. Historical events have therefore contributed directly to an awareness around the idea of Britishness and what the term in itself came to convey. Furthermore, modern factors like decolonialisation, post war immigration, joining Europe and the close relationship to America have affected what it means to be British. Thus, Britishness has developed and changed over time.

A common notion among several historians is that Britishness was something that was superimposed as a national identity in the early phase of the Union. Already a century before the political union when King James VI of Scotland became King James I of England and Scotland in 1603, he began a project of trying to unify the Scots and the English, attempting to create a union of “hearts and minds”. He made flags and coins in his aspiration to have the two nations bond. But King James’ Britishness project failed. Identity was something the population of the two nations had to feel passionately for and not be told to feel for. Nevertheless, there were a few unifying forces that could be labelled truly British as the centuries wore on and Britain began to make a mark in the world.

Forces Determining National Identity

Values and identity are often connected to large, often abstract issues that can contribute to create certain sentiments in a population. For Britons, history and the country’s former greatness certainly form the basis of contemporary British national identity.

Protestantism was apparently the strongest point of identification for Britons since they saw themselves as being different from their continental Catholic neighbours, first and foremost France. And this means Protestantism in a wide sense, not only in a religious context, but equally much the ways in which Protestantism shaped British people’s lives and values. At the same time, it helped Britons to identify their enemies, suggesting that Britain could measure itself against a Catholic axis, from Ireland to Spain, France and Italy. Standing together against this ‘outer enemy’ strengthened Britain’s national identity. There is no doubt that this inner strength helped Britain survive and triumph in two world wars, even though the enemy in the wars was never Catholic.

Trade and commerce was regarded as a typical British activity and the ways in which profits were invested gave Britain a commercial image that very much became part of British society. A liberal attitude towards market forces and direct encouragement of entrepreneurship led to a ‘monied’ interest that drove Britain towards industrialisation. Furthermore, trade, profits and a general increase in wealth resulted in a new infrastructure that tied the nations of Britain closer together, increasing the feeling of a British togetherness at the expense of national interests.

By the time of “The Great Exhibition” in 1851, which in itself was a landmark of British pride and identity, Britons directed much of their Britishness into the evolving Empire. The extended use of symbols, flags and other emblems around the world fortified the British identity and towards the end of the 19th century, the British people considered it important to bring their values out into the world. British relative greatness and their own assumptions about themselves indeed strengthened the feeling of what it meant to be British and their code of conduct was something they felt should be copied by others.

Britishness into the 20th Century

But as we move into the 20th century, it is reasonable to argue that Britishness changed, especially after World War II. The two world wars held the Union together and enforced the bonds between its inhabitants. In World War II, Prime Minister Winston Churchill used political rhetoric and symbolic power of language that struck a chord with the British population. In one of his famous speeches he pays tribute to the men of the Royal Air Force (RAF) who were currently fighting the Germans in the Battle of Britain: "Never was so much owed by so many to so few."

In the mid-war years, however, the prime symbol of Britishness, the Empire, had begun to falter. Hence, national identity changed after 1945 and two of the most important reasons may be seen as two sides of the same issue: the dissolution of the Empire and the beginning of mass immigration. Immigration changed the face of British society and white Britons had to accept new interpretations of Britishness, not always without difficulty. This is demonstrated in Andrea Levy's [i]Small Island[/i], a novel and BBC adaption. In the story we meet Gilbert, a Jamican immigrant, who rushes to the rescue of what he terms his "mother country" during the Battle of Britain by signing up for - to freely quote Churchill - "the few who helped so many", the RAF. His efforts are not met with the gratitude that one might expect.

Patriotic feelings binding Britons together got a new boost, though, in 1982, when Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher declared war against Argentina over the supremacy of the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic. The war lasted for two months and was considered a great victory for Britain, which regained control of the islands. Thirty years after the war, though, the controversy between the two countries seems to have reached a new height. The prospect of oil reserves in the ocean surrounding the islands has stirred patriotic sentiments once again. Read more The Falkland Islands Dispute.

The physical location of Britain – as a nation of islanders – has had and still has an impact on their relations to other countries and thus their feeling of Britishness. One thing is their “cousin”, the United States of America, but their neighbours on the continent are another matter. Even if Britain joined the European Union (EU) as early as in 1973, “Euroscepticism” towards their continental family is quite prevalent. In their relations with the EU, Britian is often considered as “the reluctant bride”, with their fierce resistance to join the monetary union as the predominant example.

However, the institution of the Monarchy has survived all the changing notions of national identity and Britishness. Both historically and today, the Monarchy has been a consolidating factor for the Union and the Monarch is viewed particularly as a focal point of common British reference. Britons identify both positively and negatively with the Monarch, making the institution a stable force in the country’s changing times.

Tasks and Activities

British Values and Identity - Tasks

Further Reading

The Rise and Fall of the British EmpirePost-War Immigration to Britain

Films and TV Series

- This is England

- The Remains of the Day

- Brassed off

- Britain’s Burning

- [i]The Iron Lady[/i]

- Black Adder

- Yes, Minister

Literature

[i]Small Island[/i]

[i]1964[/i]

Speech

Winston Churchill – We Shall Fight on the Beaches