The Orange and the Green, Folk Song

For a general overview of the conflcit, we recommend that you revise Northern Ireland – The Troubles

Vocabulary

approximately, assignment, civil, constitutional, contradicting, contribute, cooperate, exclusive, framework, implement, incidents, integrate, intense, intensified, interpretations, isolated, justify, mutually, options, prime, restore, significance

In this English social studies course, we are going to focus more closely on this conflict.

Unionist-Protestants and Nationalist-Catholics

Many find the conflict in Northern Ireland incomprehensible. But in principle the picture is relatively easy to understand. There are two groups of people – the Unionists who are mainly Protestants (also referred to as Loyalists) and the Nationalists who are mainly Catholics (also referred to as Republicans) – fighting over the same land. The Unionists would like the province to remain part of the United Kingdom (that explains why they are commonly called Loyalists) while the Nationalists would like Northern Ireland to be reunited with Ireland (which explains why they often are termed Republicans). Both groups claim to have a majority supporting their view; the Unionists on the grounds of being in the majority in Northern Ireland and the Nationalists on the grounds of being in the majority on the island of Ireland. Therefore, the two groups’ views do not only differ, they are mutually exclusive.

History Unites and Separates

The people of Northern Ireland, regardless of affiliation, do not necessarily disagree about historical incidents, but their interpretations of them differ greatly. Different historical accounts, which have been passed down from generation to genereation, have intensified the level of conflict and kept the groups isolated from each other. The two groups have used the past in an attempt to explain the present, but also with regard to winning the argument for the future. Past grievances are used in the present to justify claims for control of the province’s future. In other words, in addition to actual fighting, including killings, uprisings, violence and revenge, the two sides in the conflict have been locked in a propaganda “war of words” battle.

England and "The Irish Question"

Northern Ireland came into existence in 1921 as a result of centuries of conflict between the English, and later the British, and the Irish. In 1541, the English king, Henry VIII proclaimed himself King of Ireland. After the English Reformation, Henry was afraid that Ireland would be used as a springboard for an invasion from Catholic France and Spain of the then Protestant England. Henry averted that threat, and to take control of Ireland, Henry and later monarchs sent, or "planted", settlers to colonise parts of Ireland (this policy is referred to as plantation). It was particularly the North, called Ulster, that was attractive because of the fertility of the land. During the 17th and 18th centuries many English and Scottish settlers (Protestants) settled in Ireland and gradually took full political control of the country. But the Irish fought a continuous battle to keep the British out. In 1801, the British included Ireland in the Union, consisting of Wales, England and Scotland. The London Parliament thought that the “Irish problem” would disappear if Ireland came into the Union, but they were wrong. Ireland never wanted to give up the fight for self-control and independence. Throughout the 19th century, the Irish fought for Home Rule, and an internal parliament in Dublin. Many British Prime Ministers struggled with the Irish question, which in fact was twofold. Firstly, what sort of relationship should Ireland have with the Union? Secondly, what about the relationship between the Protestants in Ulster and the rest of Catholic Ireland? After the Irish Independence War of 1919-1921, the divisions in Ireland became clearer between those who wanted Home Rule for Ireland and those who wanted to remain part of the Union.

Eire and Ulster

The Peace Treaty after the Irish Independence War divided the island of Ireland in two political parts – an independent Irish Free State (Eire) and Northern Ireland (Ulster) that was to remain part of the United Kingdom due to a majority of Unionists in Ulster. The division followed religious lines; within Northern Ireland there was a majority of approximately 60 % Protestants compared to over 90% Catholics in the Irish Free State. The division of Ireland is commonly referred to as the Partition.

The Troubles

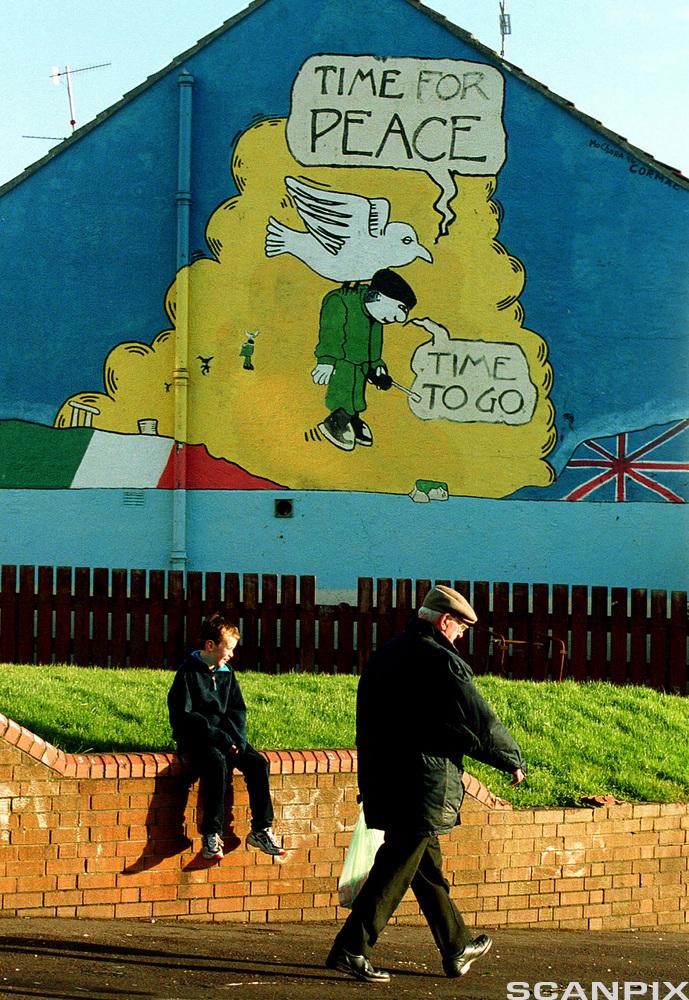

There is no doubt that the Unionist-Protestants in N. Ireland took advantage of their majority, as they in the following five decades systematically discriminated against the Nationalist-Catholic minority. By the late 1960s, there was a feeling among the minority that they had been pushed into the margins of society and turned into second-class citizens. Inspired by the Civil Rights Movement in America, the Catholics took to the streets to demonstrate against suppression and bad treatment. The marches got out of hand and there were intense and bitter clashes between radical elements from both sides. The years of 1968 and 1969 have later been called the beginning of the period known as “The Troubles” – a thirty year long civil war between Republicans and Loyalists. In 1969, the British government sent in troops to restore order on the streets of Northern Ireland, but the violence just escalated. The arrival of British troops angered the Republicans as they viewed the troops as another force sent in to keep them down. It also provoked the militant wing of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) – the Provisional IRA – a paramilitary Republican organisation that fought for freeing Northern Ireland from British control. For the next thirty years the province was thrown into a “Long War” where people lived with terror, threats and violence.

The Good Friday Agreement

In 1998, the political parties in Northern Ireland and the two governments of the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom signed a peace treaty called the Belfast Agreement (Good Friday Agreement) which brought relative peace to the province. But it turned out that the Agreement was difficult to implement and a renegotiated agreement was signed in 2007. It is this agreement, the St Andrew’s Agreement, that forms the basis for Northern Ireland’s political framework, still as an integrated part of the Union.

It is often said that the conflict in Northern Ireland is religious, especially since most of the Catholic minority want to be reunited with Catholic Ireland and that most of the Protestant majority aspire to remain part of the mainly Protestant Britain. However, the modern conflict, although containing religious arguments and terminology, is not primarily religious. It is rather about two different political identities seeking two different options with regard to constitutional belonging. Even though many Catholics are still unhappy about the situation, there is now much more equality in the region. Moreover, there are many attempts to integrate the two traditions both in sports, education and even politics, something that will contribute to build a better future. Since 2007, Northern Ireland has had a stable internal government (Stormont) where former enemies now cooperate to make sure that the province will avoid falling into the pitfalls of the past. Without a doubt, the most important desire for the future is peace, whether the province remains part of the Union or whether it is reunited with Ireland.