1964

Ahdaf Soueif (1950-)

Ahdaf Soueif was born in 1950 in Cairo, Egypt. While growing up, she attended schools and universities in Cairo and London.Her British citizenship defines her as a British novelist; nevertheless, due to her background in two cultures, her work draws upon both Arabic and British literary traditions. She has written several novels, short stories and essays and made TV appearances as cultural and political commentator of Egyptian history and Middle East politics. Many of her novels and short stories are based on incidents in her own life. Her characters range from early 20th century to late 20th century females who experience love, sexual politics, loss, Western antagonism and cultural duality.

The short story “1964” is set in England in the 60’s where the teenage Aisha is bullied and discriminated against by her ignorant English peers and teachers due to her Egyptian background.

Plain text

1964

I stood in the snow, freezing and waiting for the bus. I was lonely. I had woken up at six as usual, washed and dressed in the cold dark while my young sister and brother slept on. I had poured myself some cornflakes, smothered them in sugar and eaten them. Then I had let myself out of the back door and walked to the corner of Clapham High Street to wait for the thirty-seven.

The snow was deep around my ankle-high, fur-lined, black suede boots inherited from my mother. Or rather, I suppose now, donated by my mother while she wore ordinary shoes in the snow. Fourteen, with thick black hair which unfailingly delighted old English ladies on buses ('What lovely, curly hair. Is it natural?') and which I hated. It was the weather; hours of brushing and wrapping and pinning could do nothing against five minutes of English damp.

I loved Maggie Tulliver, Anna Karenina, Emma Bovary and understood them as I understood none of the people around me. In my own mind I was a heroine and in the middle of the night would act out scenes of high drama to the concern of my younger sister who had, however, learnt to play Charmian admirably for an eight-year-old.

We had come to England by boat. My father had come first. My mother had had trouble getting her exit visa. It was the New Socialist era in Egypt and there had been a clampdown on foreign travel. Strings were pulled but a benign bureaucracy moves slowly and it was two months before we were allowed to board the Stratheden and make for England.

We got on at Port Said. The Stratheden had come through the Suez Canal from Bombay and before that from Sydney. It was full of disappointed returning would-be Australian settlers and hopeful Indian would-be immigrants and beneath my mother's surface friendliness there was a palpable air of superiority. We were Egyptian academics come to England on a sabbatical to do Post-Doctoral Research. I wasn't post-doctoral, but it still wasn't quite the thing to play with the Indian teenagers, particularly as among them there was a tall, thin seventeen-year-old with a beaked nose called Christopher who kept asking me to meet him on deck after dark. In a spirit of adventure I gave him my London address.

I was summoned into my parents' room, where the 24 letter lay on the desk. It was addressed to me and had been opened. It never occurred to me to question that. It said that it had been respectfully fun knowing me and could he meet me again? It had a passport-size photograph of him in it. My parents were grave. They were disapproving. They were saddened. How had he got my address? I hung my head. Why was it wrong to give him my address? Why shouldn't I know him? How had he got my address? I scuffed my shoes and said I didn't know. My lie hung in the air. Why had he sent me a photograph? I really didn't know the answer to that one and said so. They believed me. 'You know you're not to be in touch with him?' 'Yes.' There were no rows, just silent, sad disapproval. You've let us down. I never answered his letter and he never wrote again - or if he did I never knew of it.

I was not troubled by the loss of Christopher. Just by the loss of a potential adventure. Anything that happened to me represented a 'potential adventure'. Every visit to the launderette was brim-full with the possibility of someone 'interesting' noticing me. When I slipped and sprained an ankle, the projected visits to the physiotherapist seemed an avenue into adventure. But the old man massaging my foot and leering toothlessly up at me ('What a pity you don't slip more often') was more an ogre than a prince and after one visit my ankle was left to heal on its own.

The likelihood of my actually arriving at an adventure was lessened by the eight-thirty p.m. curfew imposed by my parents ('Even in England it's not nice to be out later than that, dear'). But no path to rebellion was open to me so I waited for something to happen obligingly within the set boundaries.

Days of calm Clapham harmony passed and I was fretting - 'moping', my mother would say. Nothing ever happened. Life was passing me by. Then one day, when I returned from the launderette, my mother said that some young people, the Vicar's children from down the road, had come by and asked if I would like to go out with them that evening. She had said yes for me. I was thrilled.

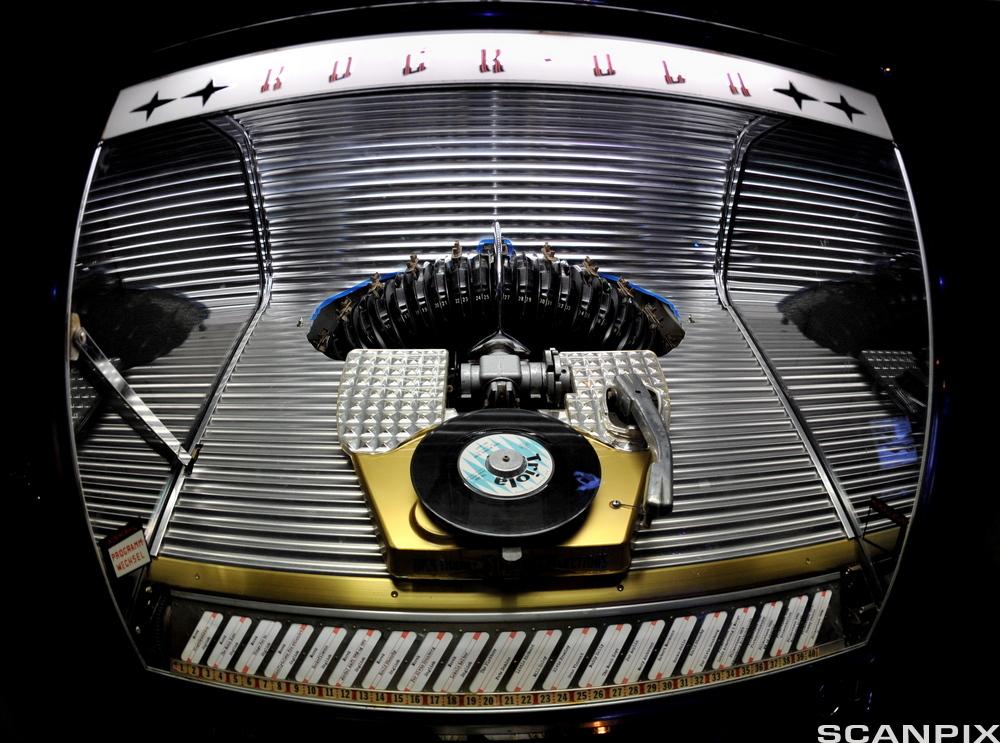

They came to collect me. Two tall and angular girls with vanishing eyebrows and hair pulled back into pony-tails and a boy with extremely short hair and glasses and a brown check suit. My knowing heart made a little motion towards sinking, but I was resolute. I was going out with three 'young people of my own age'. I did not know where we were going but the possibilities were infinite. We might go down to the cafe at the end of the road and play the juke box; I had looked through the window and seen it gleaming. We might go to a movie ('It's called a "film", dear'). We might go to a youth club; I had heard of those and imagined them to be like the Gezira Club at home, only much more exciting and liberated. Instead, we went to church.

It was not even an old and picturesque church. It was modern and bare and the benches were miles away from the pulpit and my new friends' father preached for a long, long time. I told myself it was nice that they thought nothing of taking me, a Muslim, to their church.

It was proof that I belonged - a little; that I wasn't as different as I feared I was. We all prayed. I knew about prayers from books I had read and made the appropriate movements, and when we bent our heads and closed our eyes, communing silently with God, I prayed for something to happen to relieve the awful tedium of life. I knew it was slightly incongruous to ask for excitement in church, but I was desperate.

'Friends,' the Vicar said, 'in our city today we find increasing numbers of people who come to us from far places: from alien races, alien beliefs. There are some of those among us tonight. Should any person in this congregation wish to join with us in the love of Jesus Christ, let them raise their hands now while the eyes of everyone are closed in prayer and I will seek them out later and guide them into the love of Our Lord. Raise your hand now.' I kept my eyes closed tight and my fists clenched by my sides. I could not swallow. There was no doubt in my mind that he meant me.

Afterwards we all had tea in a hall somewhere in the building. Everybody was large and pale with straight light brown hair and tweeds. I felt excessively small and dark and was agonisingly conscious of my alien appearance, and particularly my alien hair, as I waited to be sought out and guided into the love of Jesus Christ.Mercifully, it did not happen. Even so, I had been - however unknowingly - betrayed, and I knew I would never go out with the Vicar's children again.

On the way home I kept my eyes open for the Teddy boys and the Rockers preening themselves on the street corners. My heart yearned after them, with their motorcycles and their loud and gaily-coloured girlfriends. They were all that I was missing and every time I walked past one, my heart would thud in anticipation of his speaking to me. It was hopeless, I knew. My parents would never allow me to make friends with them. And when a crowd of them whistled at me one day, I knew it was even more hopeless than that. For they were hostile. And I realised that with my prim manner and prissy voice they wouldn't want me for a friend anyway. I was a misfit: I had the manners of a fledgling westernised bourgeois intellectual and the soul (though no one suspected it yet but me) of a Rocker.

After I had refused a few times to go out with the church children ('But you're always moping around complaining you don't know anybody'), temporary rescue came from some friends of my parents. We went to visit them and it turned out that they had a son three years my senior. They suggested (I was sure to his annoyance) that he take me to the theatre. My parents had no choice but to give their consent there and then, and arrangements were made for later in the week. Oddly though, I still had to get formal permission to be out late. Permission to go to the theatre apparently did not automatically include that. After all, one could always get up in the middle of the first act and be home by eight-thirty. However, permission was granted, but at ten-thirty on the dot I had to be home. I bathed myself like a concubine in our sit-down bath and went out dressed to kill in white gloves and a tartan kilt. There were lots of awkward silences. Hobson's Choice ended at ten. David suggested we have something to eat but I had to get from Waterloo to Clapham in half an hour, so food was out. There followed a rush to get home and though he kissed me goodnight in our front garden he never asked me out again. But I had had an adventure: my first-ever kiss. I had felt nothing at all, but I became more and more a heroine and borrowed from the library Mills and Boon romances which I read by torchlight under the bedcovers in the dead of night.

By now my parents had decided that the best thing to do with me was send me to school. I was meant to be studying at home for my Egyptian Prep. certificate at the end of the year, but at school I would use all my time constructively. I would also meet people my own age and make friends. I looked forward to it. I had always been happy at my school in Cairo and had no misgivings about this one. Besides, schools in books like The Girls' Annual all seemed jolly good fun. Because of their liberal, enlightened ideology and that of their friends and advisers, my parents decided to put me m a comprehensive - in Putney.

So, here I was. It was early '64. The Beatles yelled 'I wanna hold your hand' and shook their long, shiny black hair and their hips; the Mods and Rockers zoomed through the streets in their fancy gear; and I stood in the snow on the thirty-seven bus stop, on the outside, looking in.

My first contact with school was with the dark cloakroom lined with rained-on navy blue coats, berets and boots.

My second was with the long, windy corridor you had to walk through without your coat to get to the main body of the school.

My third was with thousands of uniformed girls in a huge hall singing about fishermen.

No one had warned me it was a girls' school. I had always been in a mixed school at home and found boys easier to get on with than girls. Suddenly school didn't seem like such a good idea; a vast, cold place with thousands of large girls in navy blue skirts.

'You can be excused from Assembly on grounds of being Mohammedan,' whispered the teacher who had brought me there. No fear. I wanted nothing more than to merge, to blend in silently and belong to the crowd and I wasn't about to declare myself a Mohammedan, or even a Muslim, and sit in the passage looking bored and out of it with the Pakistani girls wearing their white 30 trousers underneath their skirts. 'It's all right,' I said. 'I don't mind.'

My attempts at fading into the masses were unsuccessful. During the first break I was taken to Susan, the Third Form leader.

'Where you from?' She was slight and pale with freckles and red hair.

'From Egypt.'

'That's where they have those Pharaohs and crocodiles and things,' she explained to the others. 'D'you go to school on a camel?' This was accompanied by a snicker, but I answered seriously,

'No.'

'How d'you go to school, then?'

'Actually, my school is very near where I live. So I simply walk.' As I said this I was conscious of ambiguity (I even knew the word for it): I had not made it clear that even if school were far away I still wouldn't go on a camel. I started again:

'Actually, we only see camels -'

'D'you live in a tent?'

'No, we live in a Belgian apartment block.'

'A what?'

'An apartment block owned by a Belgian corporation.'

'Why d'you talk like that?'

'Like what?'

'Like a teacher, you know.'

I did know. I knew they were speaking Cockney and I was speaking 'proper English'. But surely I was the one who was right. My instincts, however, warned me not to tell them that.

'How many wives does your father have?'

I bridled. 'One.'

'Oh, he don't have ten, then? What does he do anyway?'

'Both my parents teach in the University.' A mistake this, one I would live to regret; I was affiliated to the enemy profession.

'Oh, teachers are they?'

'In the University,' I supplied.

'Sarah's Dad's an engineer. He makes a hundred pounds a week. How much does yours make?'

Sarah's Dad was obviously the financial top dog in the Third Form. But what was I supposed to say? Nothing, actually, he lives on a grant? But don't you see, we're intellectuals, we're classless? You can't ask me such a vulgar question?

'I don't know.'

'Well, d'you have bags of money?'

I heard my mother's voice:

'We spend our money on travel, books, records, on culture . . .'

This was met with silence. Then:

'D'you have a boyfriend?'

Again I heard my mother's voice:

'I know boys who are friends.

' 'D'you have a special boyfriend?'

I thought quickly. David hardly qualified as my boyfriend. But, for status, I lied:

'Yes.'

'D'you kiss him?'

'Do I what?' I stalled. I didn't really want to share that. And something told me it would unleash other questions I wouldn't be able to answer.

'D'you kiss him?'

'No.'

'D'you sit on his knee?'

'No.'

'Well, how far have you got then?'

'We went to the theatre,' I said. They lost interest at that point. Just moved on and never paid me much attention again. There was a girl there with blue eyes and straight black hair and her second name was Shakespear. I could have made friends with her, I thought. But she was Susan's best friend and I would not compete.

School was a disaster. The white girls lived in a world of glamour and boyfriends to which I had no passport. The black girls lived in a ghetto world of whispers and regarded me with suspicious dislike. I was too middle of the road for them. There was one girl of Greek parentage, Andrea. She came home with me one day. She came into our kitchen as my mother was preparing dinner. 'Cor blimey!' she cried. 'Olives. Can I have one?' Smiling kindly, my mother pressed her to take several. But to me she seemed unmitigatedly gross and although I was polite to her, I could not make myself be her friend.

Academically, it wasn't much better. I only scraped through most subjects and was terrible at maths. I couldn't understand why at the time because I was doing fine with the maths I was studying at home on my own. Looking back, I realise it was because I didn't know the terminology in English. The teacher was a harassed, birdlike man in white shirtsleeves, with huge eyes swimming behind his rimless spectacles, and he looked so helpless that it never occurred to me to ask him for help.

As for brilliance, I could not have chosen an unluckier subject to excel in: English. The class would have forgiven me outstanding performance in science or sports, but English? And Mrs Braithwaite, with her grey bun, her glasses over sharp, blue eyes, her tweed suit hanging lower at the front than it did at the back, booming out, 'The Egyptian gets it every time. It takes someone from Africa, a foreigner, to teach you about your native language. You should be ashamed.' At first I was proud and thought how dumb they were not to know that birds of a feather 'flocked together', that worms 'turned' and that Shylock wanted his 'pound of flesh'. But as the hostility grew I realised I had made another mistake. I tried to fade into silence, but it was no use. Those sharp, blue eyes would seek me out and she would call me by name, and I was not humble enough to give a wrong answer or say I didn't know.

Meanwhile, at break, I wandered round the cold playground, yearning for my sunny school in Cairo, and soon I learned to smuggle myself into First Lunch where I would quickly bolt down shepherd's pie and prunes and custard, then slink off to the library. There, hidden in a corner, holding on to a hot radiator uninterrupted by cold blasts of air or reality, I communed with Catherine Earnshaw or pursued prophetic visions of myself emerging, aged thirty, a seductress complete with slinky black dress and long cigarette holder with a score of tall, square-jawed men at my feet.

At sports time, however, I was not so lucky. I clambered nimbly enough up and down ladders in the gym but we often had to go out on to the playing fields for games of hockey. Why hockey? I asked. Why not tennis, or handball? No. Hockey was the school game and that was what we played. The weather was cold and grey and damp. The cold made my bones chatter, the grey depressed me and the damp made my hair curl. The hockey sticks terrorised me. I had visions of them striking my ankles, my legs, bare and goosefleshed in my gymslip. I lurked on the sidelines, shivering and protecting my legs with my hockey stick. There was no escape. And it was too cold to dream.

My parents were satisfied. I could not admit failure or disappoint them by telling them I was miserable at school so I dwelt on the treasures in the library and my achievements in the English lessons with a smattering of information on films we watched in history and geography. The rest, when questioned, came under the broad heading 'OK'.

As a mark of approval, I was given a tiny Phonotrix tape recorder with which I taped songs from Top of the Pops and Juke Box Jury. I taped them through the microphone and the sound I got was terrible, but I could hear through the distortion and I played 'Can't Buy Me Love' and 'As Tears Go By' incessantly.

Music was magic to me and every day as I walked home from the bus stop I would peer through the net curtains at the juke box gleaming against the wall in the corner cafe. It was a dark, different world in there; there were square tables with plastic covers chequered in green and white. On each table were plastic pots of salt, pepper, mustard and tomato ketchup. At the tables sat silent old men in cloth caps and jackets and shirts with no ties. One day I pushed open the door. There was a single chime and I walked in.

My heart was pounding and I couldn't see very clearly at first. The counter at the far end floated in a haze. I walked up. A large man in a striped apron stood behind it. I put a shilling on the counter and asked for a cup of tea. He pushed sixpence and a cup of tea back at me. I carried them over to a table in the corner and sat down. When I had got my breath back I stood up again and walked over to the juke box and studied the titles. Here I was on familiar ground. I put in my other shilling and selected three records. I didn't drink my tea. It was strong and white and not like the tea I was used to at home. But I was happy. When the songs were over I walked out and went home. I never told anyone about my adventure. But every three days, when I had saved one and six from my pocket money, I stopped on the way home at the corner cafe, bought tea I never drank, and played the juke box. The Beatles, the Stones, the Animals, Peter and Gordon, Cilla Black, the Swinging Blue Jeans, the Dave Clark Five. I played them all. And for the duration of three songs I was happy and brilliantly alive.

My secret bursts of life at the corner cafe sustained me but at school things got steadily worse. The atmosphere in English was becoming intolerable and I could hardly believe my own stupidity at maths and science. My hiding place in the library was discovered and I was often yanked out and deposited in the middle of the playground. My legs got knocked with the hockey sticks. The white girls lived their lives and the coloured girls lived theirs and I hovered on the outskirts of both. Then, one day, the St Valentine Dance was announced.

I was terror-struck and elated. All these girls would turn up in their designer clothes with their sophisticated 37 boyfriends. They would glide with ease on to the dance floor and do the Shake. Would I be a wallflower? Unwanted? Again the odd one out? I never dreamed of not going. The world of glamour, passion, excitement and adventure was going to be revealed for an evening. It was going to come within my reach and I would certainly be there to grasp it.

I got permission to go to the dance, and Very Special Permission to stay out until eleven o'clock. I asked David, the only boy I knew in London, to come with me. My mother bought me my first pair of high-heeled shoes: 'Ie talon bebe' the style was called, and the heels were just one and a half inches high.

February 14th finally arrived. My hair was shining, my turquoise silk dress with the high Chinese collar was enchanting and I had nylon stockings and high-heeled shoes. David came to fetch me in a dark suit and had a Pepsi with my mother before we left. He had borrowed his father's car, so we drove to Putney in style. I played it cool, as though, for me, every night was St Valentine's night, but in my head was a starry, starry sky.

We got to school and made our way to the Assembly Hall. School was transformed. It was no longer dull and cold and hostile. It was vibrant, throbbing, every door, every corridor leading to the magical place where the dance was to be held.

It was eight o' clock as we walked into the hall. The lights had been dimmed and the loudspeaker was beating out 'Come right back, I just can't bear it, I got some love and I long to share it,' and nobody was on the dance floor. All the girls were there. They were in party clothes and stood grouped together at one end of the hall. At the other end, huddled in tight, nonchalant groups in dark suits, were the boys from Wandsworth Comprehensive, our sister school.

The situation slowly sank in. None of the girls had brought a boy with her. After all the brave talk about kissing and sitting on knees, no one had actually brought a boy with her. They were all standing there, tapping their feet and hoping that the boys from Wandsworth would ask them to dance. And the boys were nervous, pretending they didn't know what they were there for, and chatting to their mates.

We joined some girls from my class for a while but conversation was awkward and we ended up standing alone by the wall. I tried to enjoy the music but it felt dead and flat. David asked me to dance but I knew he was being dutiful and besides I was too shy to be alone with him on the floor.

Time passed as I hung on waiting for something to happen while the evening slowly crumbled away and the stars went out one by one. I knew now there was no hidden world, no secret society from which I was barred. There was just - nothing.

A week later I stood as usual at the bus stop in the cold morning. I waited a few moments for the thirty-seven, then I turned back and walked home. When my mother woke up she found me sitting in my school clothes in the kitchen with a fresh bowl of sugared cornflakes in front of me.

'Aisha! What's the matter? Are you ill?' she asked.

'No,' I said.

'Well, what's the matter? Why aren't you at school?'

'I'm not going to school any more.'

'What?'

'I'm not going to school any more.'

'Have you gone crazy? What's the matter with you?'

'I'm studying for my Egyptian Prep., aren't I? I'll concentrate on that.'

'But why won't you go to school?'

'I don't want to.'

'But why?'

'It's just not worth it.'

'But you liked it so much -'

'I hated it.'

'What on earth will your father say?'

'. . .'

'He'll be very angry.'

'I'm not going to school any more.'

She told my father. She carried back protests, even threats: 'Daddy is terribly displeased with you,' then, 'Daddy won't speak to you for weeks.' Withdraw all your love, I thought. I won't go back. They went against their principles: 'You won't get any more pocket money.' It was still no good.

Every morning my parents went to the University and my sister and brother to school. I would draw up my father's large armchair in front of the television, carry up some toast and butter, and watch the races. Or I would switch on my Phonotrix and dream. Or read. The whole house was my territory from nine in the morning to five in the afternoon and I lived my private life and was impervious to the cold, disapproving atmosphere that pervaded the evenings. After a couple of weeks they gave up.

One day I discovered a secret cache of books hidden in my parents' bedroom. Fanny Hill, The Perfumed Garden of Sheikh Nefzawi and the Kama Sutra. My rebellion had paid off in grand style. I spent my fifteenth year in a lotus dream, sunk in an armchair, throbbing to the beat of the Stones, reading erotica.

And I passed my exams.