The Usual Rules

Joyce Maynard is an author and columnist based in California. Her novel, The Usual Rules, was chosen as one of the best books for young readers in 2003.

- Read the texts provided on Joyce Maynard´s website about her novel.

- Read the excerpt on our site, The Usual Rules,

About The Usual Rules by Joyce Maynard

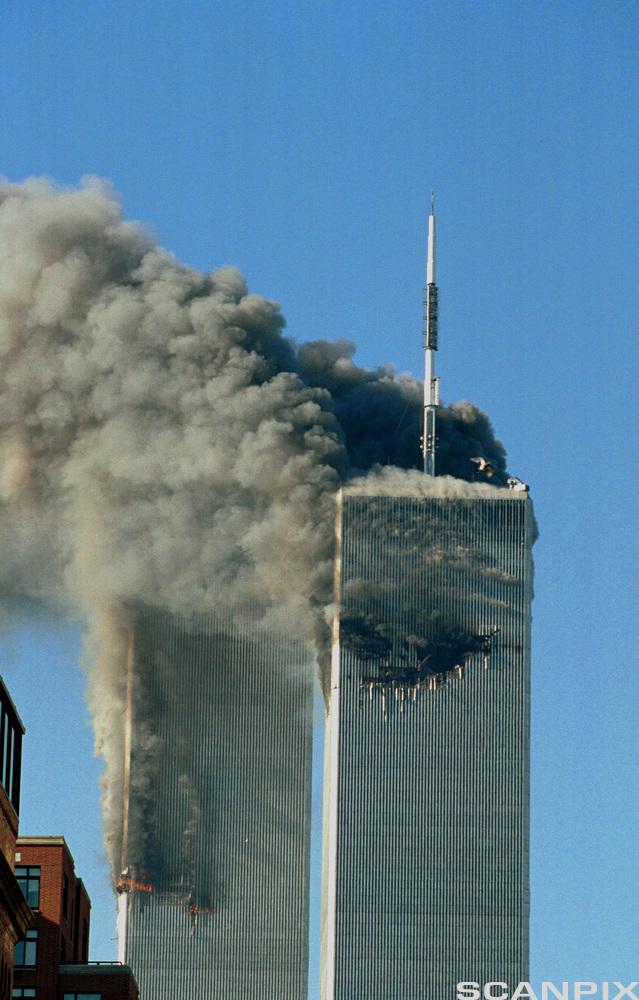

It's Tuesday morning in Brooklyn -- a perfect September day. Wendy's heading to school -- anxious to make plans with her best friend, worried about how she looks, mad at her mother for not letting her visit her father in California, impatient with her little brother and the almost too-loving concern of her jazz musician step-father. She's out the door to catch the bus. An hour later comes the news: A plane has crashed into the World Trade Center. Her mother's building.

Through the eyes of thirteen-year-old Wendy, we gain entrance to the world rarely shown by those who documented the events of that one terrible day: A family's slow and terrible realization that Wendy's mother has died, and their struggle to go on with their lives in the face of crushing loss.

Absent for years, Wendy's real father shows up without warning. He takes her back with him to California, where she re-invents a life that comes to include a teenage mother, living on her own in a one-room apartment with a TV set and not much else; her father's cactus-growing girlfriend, newly reconnected with her son that she gave up for adoption twenty years before; a sad and tender bookstore owner who introduces her to the voice of Anne Frank and to his autistic son; and a homeless skateboarder, on a mission to find his long-lost brother.

Over the winter and spring that follow, Wendy moves between the alternately painful and reassuring memories of her mother and the revelations that come with growing to know her father for the first time. Pulled between her old life in Brooklyn and the new one three thousand miles away -- in a world where, she has learned, the usual rules no longer apply, Wendy discovers a strength and a capacity for compassion and survival that she never knew she possessed.

At the core of the story is Wendy's strong connection with her little brother, back in New York, who is grieving the loss of his mother without her. This is a story about the tie of siblings, about children who lose their parents, parents who lose their children, and the unexpected ways they sometimes find each other again. Set against the backdrop of global and personal tragedy, and written in a style alternately wry and heartbreaking, The Usual Rules is an unexpectedly hopeful story of healing and forgiveness that will offer readers, young and old alike, a picture of how -- out of the rubble -- a family rebuilds its life.

Questions

1. Who is the main character and how is she characterized?

2. What seems to be the main setting of the story?

3. What seems to be the plot?

4. Wendy has lost her mum, what makes it particularly difficult for her to cope with the loss, do you think?

5. What is meant do you think with the expression "where the usual rules do not apply"?

Read the excerpt below from The Usual Rules. This is a few years after 9/11, and we meet Wendy who has gone from California to visit Louie (her little brother) and Josh (her step-dad) in Brooklyn. Then answer a few questions.

Excerpt

It was Saturday, raining hard, the sky gunmetal gray. Normally, Josh would be watching cartoons with Louie, but he had gone down to the armory with her mother's hairbrush and her dental X-rays--the thing he had said, at first, he'd never do.

Louie wasn't allowed to watch TV unsupervised anymore, because you never knew when they were going to break into the programming with some piece of news, and it was never good.

Louie was in the family room, eating his cereal. Nobody had gotten around to turning on the lights. Josh had taken the batteries out of the remote control, so he couldn't turn the television on. Now he sat there in his elf costume, with his cereal bowl set on the tray table they used to put their food on, video nights, when Josh had a gig and their mom let them eat their meals with a movie. His back was strangely straight, as if he was balancing a book on his head, and he was holding his spoon in midair. The way he was sitting reminded Wendy of squirrels you'd see in the park--the way one would freeze halfway up a tree, or in a patch of grass, and lock its eyes on some random spot for long seconds, before it got back to whatever it was doing before.

Come on into my room, Louie, she said. I'll read to you.

She'd told him to bring a pile of books into bed, the way her mother had done with her when she was little. They had already read Katy and the Big Snow and Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs and Curious George. Now he wanted Goodnight, Moon.

Don't you want a more grown-up book than that, Louie? she asked. Their mother used to read Goodnight Moon to him way back, when he still slept in his crib.

I want this one. He put the old familiar book in her hands. They were in her bed now. He adjusted his body so he was curled up against her tight. She started reading.

"In the great green room there was a telephone and a red balloon," she began. "And a picture of the cow jumping over the moon."

As she read the words, he placed his finger on the part of the picture she was talking about, the same way their mother had taught her to do when she was very little. When she got to the part about the quiet old lady murmuring hush, Louie put his finger up to his lips the same way Wendy used to when she was little. She'd forgotten how her mother always did that on this page.

"Goodnight room," she said. "Goodnight moon." She looked over at her brother then because his finger wasn't on the moon. His thumb was in his mouth, was part of it, and his hand was busy twirling his ribbon.

Questions

- From the passage we see that a lot of things have changed in their Brooklyn home. Jot down the changes. To which extent do you think what happened 9/11 has affected this?

- Why do you think Louie wants them to read the same old book that he used to read when he was little? What happens when Wendy reads to him and what does it mean?

- If you compare this scene with your pre-reading about the novel, how do you think the relationship between Louie and Wendy has changed.

- According to your pre-reading, comment how has Wendy changed.

Read the afterword by the author about what inspired her to write The Usual Rules. Then answer the questions.

Afterword by Joyce Maynard

In the first week of September, 2001, I left my home in Marin County, California, with the intention of spending the next six months in some remote place far from the distractions of my life to write a novel. I wasn’t sure what I’d be writing about, but my mind was much occupied by the knowledge that for the first time in twenty five years, I would have no child to care for. My nearly grown sons and my daughter were all gone from home now -- two out of three of them on other continents -- and no doubt my decision to take my leave was inspired, more than anything else, by the vast empty space their departure had left in my life. I was thinking a lot about parents and children, for sure -- about my quarter-century-long project of raising my own three, my longing to see them safe, and the growing awareness that little I could do anymore -- now or in the future -- could protect them from the risks that come with being a human being alive on this planet.

I was thinking about the scars divorce had left on all of us, the dream I had once held so dear, of children growing up under the same roof with their two original parents. And I was thinking -- as I watched my sons and daughter embrace each other at the various airports where we said our goodbyes that September, on one coast and another -- of the great gift that has been their huge love for each other, in the face of so many other uncertainties.

Before leaving the country, I stopped in New York City to pay a brief visit to my son Charlie, who was a student there. Two days after my arrival, leaving a coffee shop in midtown Manhattan, I heard the news that a plane had hit one of the Twin Towers. Nothing was the same after that for any of us of course, nor has it been.

I ended up staying in the city much longer than I’d planned, long after planes had resumed flying. As grim and terrible a place as New York had become, in those early days after the attack, it also felt important -- particularly as someone who has loved that city since the day I first set foot in it, at age ten -- to bear witness to what had happened, as much as I was able. I spent over three weeks in New York, as it turned out -- most of that time just walking the streets, taking in the names and faces on the flyers posted everywhere, listening to the conversations on the street, standing in front of those beautiful and heartbreaking altars that sprung up all over the city within hours.

Other people’s tragedy and loss remind us of our own vulnerability of course, and so I worried terribly about my younger son, off in Africa somewhere, and unreachable, and my daughter, in Central America. But I think I worried less for my children’s physical safety, over the course of those days, than about the world they and the rest of their generation were fast inheriting. Where was hope to be found? How could a young person absorb the crushing news of what we had all just witnessed? Tragedy and disaster of that scale had taken place, forever, on other shores besides our own of course, but like a lot of Americans, I had always enjoyed a certain comfortable remove from what went on far from home. That would never again be possible.

Perhaps because of the ages of my own three children, I found myself trying to fathom how, in the midst of so much tragedy and violence and uncertainty about the future, a young person could go on to build a hopeful life. I thought about the children and teenagers who had lost a parent that day. I wanted to know how a child goes on with her life -- how anyone does -- after huge and irrevocable loss of the most abrupt and senseless form. Lacking any clear answers, I decided to create a character who might help me locate them.

I don’t pretend that every child who has experienced huge losses will survive as hopeful and whole as my fictional girl has done on these pages. I only mean to offer a glimpse -- for myself, and the young people I love, and others I haven’t met yet -- of what might be possible, of the light that remains, after a season of darkness, and the spring that follows even the coldest kind of winter.

Questions

- What do you think inspired Joyce Marnard to choose a child protagonist? How do you think her personal experience has affected this choice?

- How does she explain that she chose 9/11 as a setting and coping with losses as a theme?

Jonathan Safran Foer: Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close

Read an excerpt and watch a film trailer from the novel by following this link.

Further Tasks and Activities

You will find further tasks related to Maynard's The Usual Rules and Foer's Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close by following this link.